The Paradox of Power: Madurismo on Basu's Curve

The bodies scattered in their climb to power are the chains that bind Madurismo.

Those who believe that offering Madurismo a “golden bridge” to retire to a mansion overlooking the Bosphorus will free us from their yoke and incompetence are mistaken.

Once at the peak of power, there’s no escape: they are as imprisoned as those they have condemned to jail. Their impulse is to continue ruling until death finds them peacefully in their beds, or until they are overthrown or assassinated, as happened with Ceaucescu, Somoza, or Franco.

For the dictator and his clique, power is the only goal. And therein lies their dilemma: staying in power means multiplying their violations and abuses. A spiraling dynamic that intensifies with the certainty that only power saves them from Justice.

In the 2013 presidential election, the initial voting results showed Maduro losing. While this trend persisted, I frequently heard members of the current Madurismo clique say they would never hand over power to Capriles. If that was the mindset before Nicolás became president, imagine what it is now, ten years later, with a list of crimes pending before the International Criminal Court.

Kaushik Basu, former Chief Economist of the World Bank, has pointed out that this dynamic is universal. In his work “The Transformation of Dictators: Why They Get Worse Over Time”, he models this trend based on the analysis of the Ortega regime in Nicaragua.

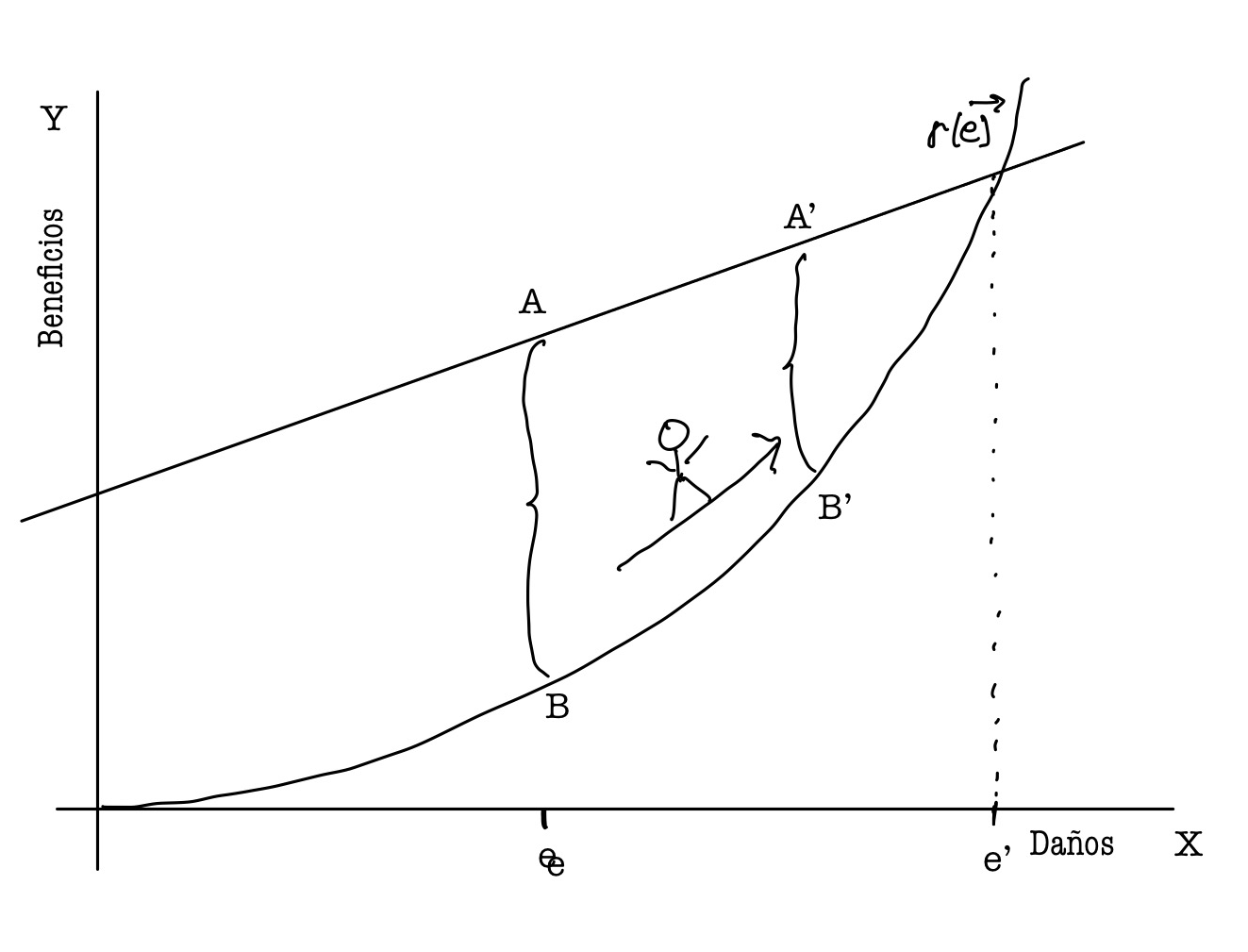

According to Basu’s model, an autocrat’s ability to stay in power is directly related to the damage (e) they can inflict on people and institutions: the greater the damage, the more likely they are to remain in power.

However, there’s a limit.

This function (e) is convex, meaning there comes a point where inflicting more damage results in diminishing returns.

Based on this thesis, I’d like to argue against the illusion of some opposition who believe that Madurismo will opt for the incentives of a golden exile instead of continuing with the delicate balance that keeps them in power; or who think they will yield to economic sanctions.

The Price of Barbados

The TSJ’s decision to annul the opposition’s presidential primary fits perfectly into Basu’s model. With this move, they progress on the cost curve associated with their perpetuation in power, while eroding their potential future benefits. Interpreting Basu, we would say this is the paradox of their power: the more they try to cling to it, the more they limit their future options.

In this scenario, with a migrating and disarticulated civil society, it is the United States that holds the real capacity to influence the costs Madurismo faces to stay in power. The relaxation of sanctions, a result of the Barbados agreement, represents the oxygen the government urgently needs. However, the price of this concession, opening a small window to democracy, is one that Madurismo is neither willing nor able to pay.

What the recent opposition primary revealed, and which sowed terror in the government, is the dimension and intensity of the rejection Venezuelans feel towards the ruling clique. The vote mobilized in these primaries is essentially a vote of rejection against the “current state of affairs”, a protest against the worst government our history has seen.

However, in the face of the government’s kick to the Barbados agreement, the United States faces a strategic crossroads: should they reduce sanctions, hoping that an economic respite will halt the migratory flow to their borders, or is it preferable to maintain financial pressure on the dictatorship?

In the face of the first crisis of the Barbados agreement, initial reactions have been mere sighs, quickly countered by swift moves behind the curtain. The move, however, reaffirms what many, including Basu’s model, point out: Madurismo will not leave power through negotiations, as their only goal is power itself. With their future in the balance, Madurismo will maneuver to minimize losses, following Basu’s curve, and will pay any price to stay in power.

The power dynamic, as described by Basu, although universal, finds a particular case in Venezuela. As the regime clings to power, Venezuelan society and the international community face an unprecedented challenge. History doesn’t offer direct solutions: it’s not just about incentives or sanctions. We are facing an entity that perceives power not only as a means but as its very reason for being. While history has shown that regimes of this nature eventually fall, the cost to the nation and its people is often high. The key lies in active and determined participation by the people, capable of creating fissures in the ruling elite.

Today, within the Madurismo elite, there are those who, in a game of finesse, lurk to displace Maduro and his clique from power. After the primaries, internal tensions have intensified in the face of a renewed realization: Maduro is an anchor around their necks. In the party’s corridors and corners, there’s a murmur of what the primary confirmed: the widespread rejection of the worst government in our history that seeks re-election with the worst possible candidate. MCM will never be a candidate, certainly, but Maduro is the least likely to guarantee a future for Chavismo. Whoever manages to displace him will have significant support, both internally and externally. The key question remains: how much more will Madurismo sacrifice, and how much more will Venezuela endure before reaching a tipping point?